🍼 China's birthrate crisis and the business of single women's fertility | Following the Yuan

On the missing piece in China's birthrate narrative

I was pregnant.

The day I took the test, I was in a northern Chinese city for a friend’s wedding and had been paranoid about a late period for days. I felt like I could see signs everywhere — from watching Leah Dou as a pregnant teenager in The Eleventh Chapter, to meeting Songzi Niangniang, the fertility goddess, once I entered a temple in Pingyao. I knew I had to do something to ease my rattled mind.

I got back to the hotel late at night and decided to order a pregnancy test from Meituan, which arrived in discreet packaging. I was somehow relieved when the Clearblue test showed a positive sign, and was soon awash by a wave of heaviness: I’m a mom now?

That continued to sit heavily on my brain, and became something I had to remind myself every morning for the week after as I caressed my belly.

I thought about a conversation I had recently with my mom about her abortion, specifically, about her having to cease her pregnancy after having me in early 1990s.

Under the One-Child Policy, which officially encouraged people to have one child, local party officials were eager to enforce much stricter guidelines with it being a core part of their KPI*. In my city in Jiangsu province, that meant all the relatives were mobilized to talk sense into them and my parents would be let go from their jobs. My mom, a teacher then, eventually went to a maternal and child health hospital to take some pills.

But her health wasn’t protected. Her post-abortion bleeding became non-stop after being sent home. She passed out after losing several basins’ worth of blood, and was sent back to the hospital. When she was lying in the hospital bed, she felt her soul leave her body, and she told me that she could see my grandma holding me from above.

Yet when I told her about my pregnancy, she smiled, and said I should keep it.

1, 2, 3: policy levers around fertility

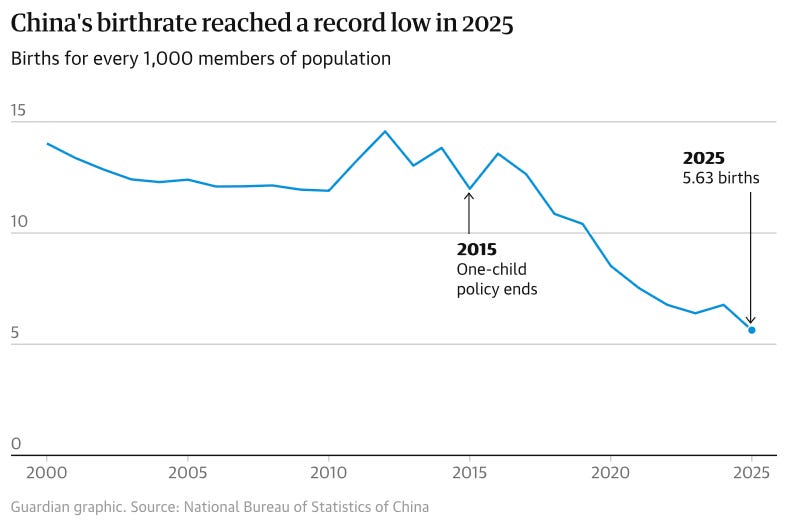

Beijing scraped the One-Child Policy in 2015 after a significant drop in birth rate from 13.83 to 11.99 per thousand. And the forthcoming Two-Child Policy brought a short-term boost before losing momentum to a long-winded and sure decline.

While being on the downward path, Beijing further relaxed the rules to Three-Child Policy in 2021, with a lukewarm reaction apart from a non-correlated bump from the Year of Dragon in 2024, an auspicious year to have babies.

Registered births in 2025 dropped to 7.92 million, down 17% from 9.54 million in 2024, and the lowest since records began in 1949, the National Bureau of Statistics reported in January.

Last July, Beijing announced the very first 3,600 yuan/year birth subsidies, payments that will be available to all families with children under the age of 3 who are born or legally adopted. Parents can apply for it through a mini-program as of late August, 2025, or apply offline at the township government or subdistrict office.

It’s too early to call this subsidy a failure, after all, policy is just one variable of people’s family planning decisions.

In a webinar I organized about this specific issue then, I listed four main driving factors behind childbirth:

Individual factor

Economic factor

Social/Cultural factor

Political factor

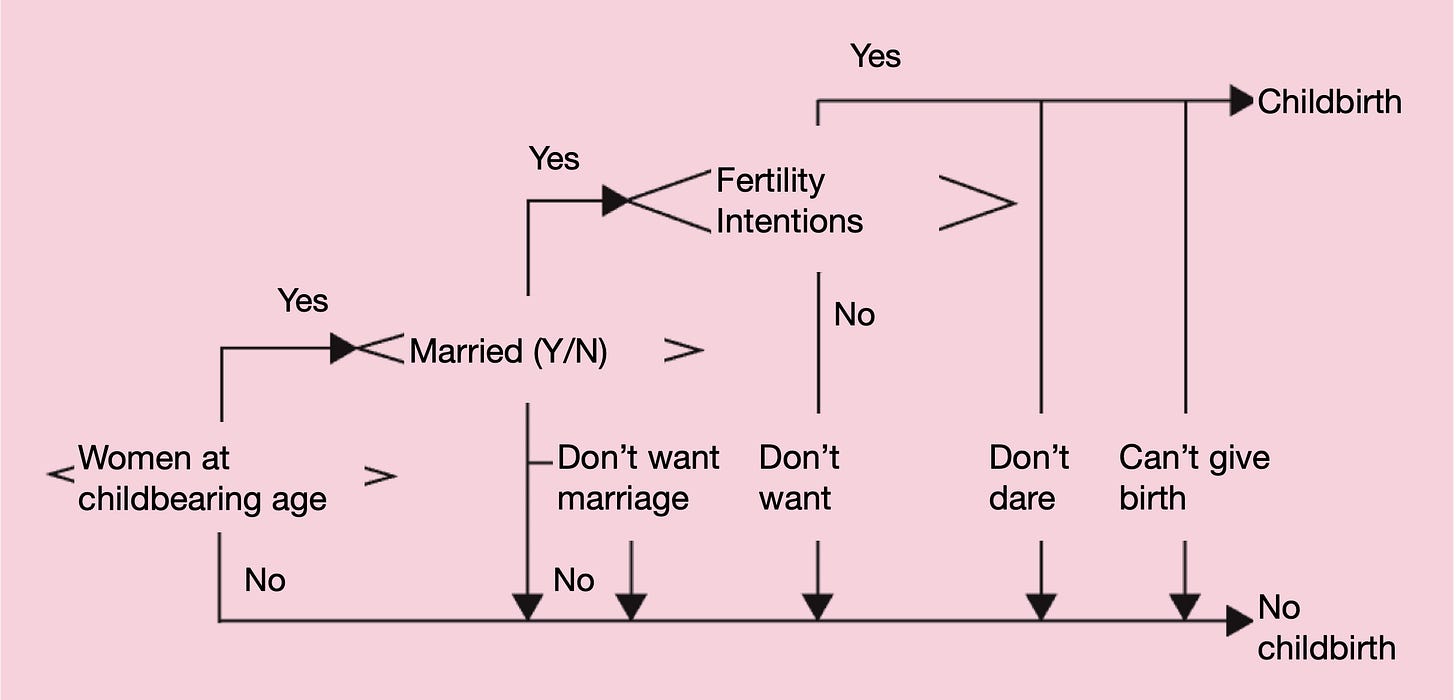

When I look at the list again today, and the chart I put into my Keynote from a 2025 Peking University paper* below, it feels personal — I’m excluded in the social category as a single woman.

The case around being single and female

In either domestic or Western media, middle class Chinese women are often portrayed as this fussy, overeducated, high-demand group who think they are too good for their male counterparts.

Women around the world complain about dating. In reality, my experience of living and dating in Shanghai for eight years altogether had been much more tougher than my years in London and New York City. China’s dichotomy of a patriarchal social structure and rising female consciousness presents a unique challenge, which results in a widely reported imbalance of undateable rural men and urban women, and those in between.

Educated women in big cities lack their equals, which isn’t just about finance and CVs, but about values. They struggle to fit themselves into the outdated patriarchal expectations of being domestic, docile and unambitious, this is often the case when they meet the wrong person.

Most often, they won’t even know where to meet that person. In Shanghai, the city that I’m most familiar with — its lifestyle attracts women from all over China, and the city center is full of FMCG, marketing, and advertising jobs that conventionally skew towards women, whereas suburban areas like Fengxian and Zhangjiang have a much larger male population, being Shanghai’s EV and tech hubs.

Sister Jing, a professional matchmaker with 500,000 followers across different platforms, told podcast The Ugly Truth last month that the perceived eligible male to female ratio in China’s first-tier cities is 1:7. I can testify to the environment that courages 雌竞 (female intrasexual competition), and although the “leftover women” narrative has been scrapped in the media in recent years, it still stands true that in China, women’s desirability is closely linked to age.

A widely cited statistics show that the number of unmarried women aged 30 and above has surpassed 42 million, and in first-tier cities, more than 35% of women aged 30–39 are unmarried. Some of these women, like me, also want to freeze their eggs; I know of people who have done it in the U.S., Malaysia, Thailand, Greece, costing from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of yuan.

According to iResearch, China’s assisted reproductive technology (ART) market is expected to grow to 48.4 billion yuan in 2026. The market mainly serves infertile, married couples. Data released by the National Health Commission and the China Population Association show that in 2021, the penetration rate of assisted reproduction in China was 8.2%, which was relatively low comparing to over 30% in the U.S. The room for growth is substantial.

The fertility funnel

I already made up my mind before the test — the person involved and I had already broke up, I knew he wouldn’t be a reliable father, and my foreseeable future was full of changes — this was not the right time.

In China, the phrase 去父留子 (remove the father and keep the child) has started to be twirled around in conversations as rising female independence becomes a symbol of power and control. However, when I put things into perspective — it’s not that easy to consciously eliminate the presence of a father from the child before they are born, nor is it easy to decide whether I’m financially and emotionally capable of becoming a single mom.

In an online response about this question, Fudan University associate professor Shen Yifei expressed her opposition to the rhetoric, as it diminishes the separate societal roles within a family: one doesn’t need to have a father, but a child must grow up with socialized child-rearing (training children to adopt societal norms) and physiological child-rearing (focuses on a child's neurobiological regulation), which can hardly be done by one person.

For women living in largest cities Beijing and Shanghai, like I was before moving to London in the summer of 2024, we lose 580 thousand yuan and six to seven years of working life expectancy to bearing and rearing one child, according to the 2020 paper* “How Large is the Motherhood Penalty in Urban China?” by Liu Jinju, an associate professor at the School of Public Administration at Beijing City University.

I suppose those were the individual and economic factors I’ve considered. In terms of social/cultural factors and political ones — they are having less effect on me after I left China.

On the surface, Beijing forbids workplace discrimination against women; in reality, it is common for women to get routinely questions during job interviews about their family planning as maternity leave is usually seen as a company’s loss. At around 30, the supposed age where they consider settling down, they also have to face a barrier known as “the curse of 35.”

Another change in culture, which may be owing to the rise of female-centric apps such as Rednote, is that more young women step forward to share the physical and psychological harms of giving birth.

Political reasons play a big part in my decision to leave. That includes my personal safety as an ex-journalist and a researcher, with fear triggered by tangential events and incidents involving acquaintances; that also includes the negligence Beijing shows to women’s safety issues (e.g. everyday voyeurism, human trafficking of adult women, etc.).

In the weeks after the now disbanded Telegram group MaskPark was brought to light, which encouraged Chinese men to share unsolicited photos of women around them. I started seeing such comments online toward the central government:

“You can choose not to investigate — and we can choose not to give birth. (你们可以不查 我们也可以不生。)”

“If [you] don’t address this, just wait for the birth rate to drop to 0%. (再不处理就等着生育率降为0%吧。)”

It would be hugely gratifying to think that the commentators manifested this year’s record-low birth rate, but I don’t think politics yields that much effect in most others’ family planning decisions. I know very well that being able to do egg freezing abroad, and having options to leave are a privilege.

In theory, I’ve been decisive in severing ties with a patriarchal home nation and the man who impregnated me; in reality, it’s much harder.

Where is China’s birthrate going?

After hearing about my story with the man, my mom softened and agreed that I should get an abortion. But for her, now the question is whether to do it in China or back in London?

She tirelessly looked things up online and found me a good deal from United Family Healthcare, that cost over 20,000 yuan and included 2 nights at the branch in Shanghai.

Here are the general abortion options depending on the age of the fetuses: medical abortion is for fetus under 10 weeks; surgical abortion is for those above. But there are also other factors at play, like pain level and certainty of getting it done in one go.

I ruled out the option to do it in China, not because of the money, but because the system is discriminatory towards unmarried women — by default, unmarried women are required sign waivers before they undergo gynecological exams because we are not expected to have sex before marriage. I’ve been given enough funny looks whenever I signed a waiver, the last thing I wanted to do now is receive secondary trauma at such a vulnerable state as a pregnant single woman.

I know that shouldn’t be a worry at private hospitals like United Family Healthcare, but isn’t it unfair, that if one requires decency, they must be able to afford a price out of reach for so many.

I did it through NHS after I went back to London (which was paid for as part of my visa application). The female doctor, who told me she has two daughters, was very caring and empathetic. I felt good about my decision.

The older I get, the more I see the necessity of an environment that champions equality, which is more than lip service and DEI slogans. Yes, we are not having our feet bound, we can go to school and we can work, but it doesn’t mean we should be complacent now.

Being pregnant as a single woman in her 30s gave me a window to see my options, and the lack thereof:

I would love not to have to sign a waiver to be able to do my gynecological exam, and I do not want to encounter any funny looks or comments while doing that;

I would love to have a safe abortion procedure done in a caring environment;

I would love to be able to do egg freezing in China, just as how single men are able to freeze their semen. [the National Health Commission said in 2000 that it carried too many health risks for women; Xu Zaozao, the face of the fight over egg-freezing rights, lost her final appeal in 2024]

I sometimes wonder whether the current state reflects the government’s attitude towards feminism, which is framed as a subversion of state power and also heavily stigmatized in civil society as “Women's Fist-ism” — even talking about female rights seem politically incorrect.

So, although Chinese women truly hold the “half the sky” role in economic and social development, as President Xi Jinping recognized at the opening ceremony of the Global Women’s Summit, from working to internet entrepreneurship to winning Olympic medals, it seems that asking for rights outside the commercial field would be overstepping. This is the contradictory stance that Beijing is in.

I don’t have an answer to the question I’m posing at the start, which is, how much would single women help solve the birthrate problem, and how big of a business would it be if single women are allowed to freeze their eggs in China?

To quote a male friend: Male violence is so overwhelming and all-encompassing, that even well-intentioned men end up damaging women’s bodies in decisions that appear utterly irrelevant to the men themselves.

Before the fertility question is considered from a woman’s perspective, as the government tends to forget that it is a women’s decision, I don’t think China’s birthrate will ever go up. 🔚

References:

Yu, Z. (2023). Municipal and county investment: The logic of economic development and investment in lower-tier regions (市县投资:下沉区域经济发展与投资逻辑). Shanghai Far East Publishing House.

Liu, J. (2020). How large is the motherhood penalty in urban China? Population Research (人口研究), 44(2): 33-43.

Shi, Z., et al. (2024). The incentive effect and the safety-net effect of birth subsidy policies: Evidence from field experiments on birth subsidies. Zhongnan University of Economics and Law.

Li, J, et. al. (2025) Re-examining China’s Persistently Low Fertility Rate from the Perspective of Dynamic Structural Differences. Peking University.

Thanks for sharing such a personal story. It helps give a pretty visceral sense of the state of attitudes towards women and healthcare’s treatment of women.

Although China is different in a lot of ways, it’s the same kind of attitudes and trends from traditional culture clashing with modern society as we see in Japan, Korea, etc… with similar results in plummeting fertility rates.

thanks for this courageous, raw, personal and thoughtful piece Yaling. Sending you many hugs.