The social contract and communication model in China's oil tank truck story 🚚| Following the Yuan

This story is just one of many hidden under China’s broken information system that will never see the light of day.

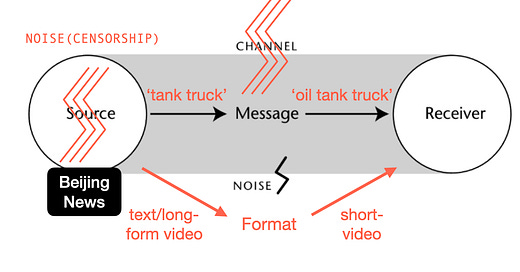

Author’s note: The recent public outcry over cooking oil revealed a dark secret in the road transportation and oil industries: industrial oil trucks are not cleaned before switching to transporting cooking oil. This scandal has been the talk of the town since early July.

This story is just one of many hidden under China’s broken information system that w…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Following the Yuan to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.