Q&A: Comparing China and India with Kyle Chan | Following the Yuan

'India is like China was 15-20 years ago', but how? To better frame my views on two of the most important consumer markets, I turn to a Princeton Sociology postdoc and lecturer.

Editor’s note: As an ex-business journalist who does business research on a daily basis, I’ve recently been asked a lot about China VS India markets.

It's been a common topic for the last two decades, but now, as India may overtake China in terms of growth (despite its $3.5 trillion economy being dwarfed by China's $17.8 trillion), Global businesses started taking this comparison seriously.

Having fully understood that a country can't be explained solely through numbers and statistics, I’ve found it challenging to answer the question in a nuanced way, because I knew nothing about India. Until I later came across Kyle Chan’s dissertation “Fast Track: State Capacity and Railway Bureaucracies in China and India”, and thought to myself “bingo!”.

Currently working as Postdoctoral Research Associate and Lecturer in Sociology at Princeton, Kyle has done dogged on-the-ground research in these two countries. Over emails, we discussed his research methods, differences in access to sources, and how exactly businesses should approach generalized comments like “India is like China but 15-20 years ago”. The conversation was enlightening and helpful for my work, and I hope it helps broaden your thinking, too. [Kyle’s newsletter: High Capacity]

Q: I’ve seen very few researchers doing comparative studies on China VS India in recent years with the extent of field research you did. From the business perspective, the Indian market is also never the top destination for Chinese companies while exploring overseas markets.

Why do you think 1. There is little scholarly research? Or correct me if I’m wrong; 2. Why are China and India markets not as connected as say, China and South East Asia, China and the Middle East?

A: The lack of comparative research on China and India is a big problem in the social sciences. These are two of the most important countries in the world, together making up a third of the world’s population. The main reason why they’re not compared to each other more often in academic research—although the China-India comparison is made all the time by everyone else—is that academics have a narrow definition of rigor and significance.

The regime type issue is the main sticking point. Usually comparisons are made between countries that are similar on many factors as a way to control for other variables. For example, comparing India versus Pakistan. Many scholars think China’s and India’s political systems are too different to make any kind of comparison useful. But I disagree.

China and India actually share so much in common: huge populations, developing countries, long proud histories, challenges with corruption and environmental issues, a cultural emphasis on education, high levels of entrepreneurship, and so on. Their modern states were even founded around the same time: India gained independence in 1947, and the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949. Even their political economies have more in common than many might think given that both come from a statist tradition inspired by the Soviet Union. To this day, state-owned enterprises play an outsized role in both countries.

China and India are less connected through business ties than what might expect given their incredible economic growth, geographical proximity, and overlapping markets. You can see this in the lack of flights between Beijing and Delhi, the capitals of the two biggest countries in the world, which were already limited before COVID and the clashes in the Galwan Valley. The problem is geopolitical. China and India have had a difficult relationship despite efforts in the early days to forge ties as major non-Western powers. Border disputes, China’s relationship with Pakistan, India’s relationship with the Dalai Lama—these are some of the problems that keep coming up as thorns between the two Asian giants.

There was a period of time recently when it looked like business and investment ties between China and India were almost flourishing. Chinese-made phones and Chinese apps were popular in India. Some Bollywood films like Dangal were popular in China. Chinese tech companies like Alibaba and Tencent were making big investments in Indian companies, like Paytm. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi had a positive visit to China and seemed to have a growing relationship with Chinese President Xi Jinping around the G20 summit in 2016. But after the deadly fighting between Chinese and Indian troops near the Galwan Valley in 2020, the relationship between the two countries really deteriorated. For example, India banned TikTok not long after, which had been wildly popular in India. I remember walking around Delhi and frequently seeing young Indians doing TikTok videos up until then. [India banned 59 China-owned apps in 2020.]

Overall, the cooling in the relationship is a shame. I believe very strongly that China and India have so much to gain from each other through economic ties. For example, India’s big push in infrastructure and manufacturing would benefit tremendously from Chinese resources and the involvement of Chinese firms. But unfortunately these geopolitical issues are a difficult reality that don’t seem to be going away anytime soon.

“Many scholars think China’s and India’s political systems are too different to make any kind of comparison useful. But I disagree.”

Q: You did 24 months of fieldwork in China and India from 2016 to 2019, so prior to Covid. You mentioned in the dissertation that your research in China met a lot of difficulties, how do you think the situation may be different today?

Doing fieldwork in China and India before Covid was an incredible experience. Spending so much time in both countries—not just in Beijing and Delhi but also visiting other cities like Chengdu and Harbin and Hyderabad and Sikkim—gave me a unique view into how these two countries really work on the ground. Getting interviews with railway officials was much harder in China than in India.

In India, I faced many challenges as well, but I found Indian railway officials more open to speaking with a foreigner and sharing their thoughts candidly. In China, I had to pull every connection I had. Many Chinese researchers warned me that they had tried to study the railways there and found it impossible. The former Ministry of Railways in China was famously closed-off and secretive, partly due to its military roots. Even Chinese reporters like at Caixin had trouble getting anyone from within the system (体制内; those within the state organs, state-owned enterprises, etc.) to speak. I eventually did manage to talk to some Chinese railway officials and managers working at railway state-owned enterprises, which I was very grateful for. But even then, I found them less willing to talk openly the way that Indian railway officials did.

Today, I can only imagine it would be even more difficult. US-China tensions have really grown. Concerns about speaking with foreign researchers have grown in China. I used to tell people in China that my family was from Hong Kong, but now even that is more of a liability because of the tensions between Mainlanders and Hong Kongers. [Editor’s note: I believe that the tension eased up a lot after the 2019 protests. The locals who decide to live there now are either apolitical or open to integrating economically, it's popular for locals to go to Shenzhen for shopping or entertainment, and of course, they tend to censor themselves quite a bit. In the research context, US researchers with HK family backgrounds won't have additional trouble as the mainland Chinese interviewees may naturally recognize them as Chinese.]

The situation is different in other areas though. On climate and environmental issues, there is definitely more openness and international collaboration. I was grateful for the research I was able to do on China’s railway system, but I think any foreigner trying to study this topic today would find it nearly impossible.

Q: What are some applicable takeaways from your research that international businesses can use to navigate China and India markets?

My biggest piece of advice for anyone who wants to do business in China or India is to find local partners you feel comfortable with and who have a strong track record of working with international firms. This may be obvious, but it’s very important. Both China and India are extremely complex countries. You can read an entire library full of books about China or India and yet still have very little feel for how things really work on the ground.

For doing business in China, it may help to know the priorities of the local and central government. This depends on the industry, business type, and so on. But it can help to understand whether, say, the local government whose jurisdiction you might be working in is prioritizing tourism or investment in a certain sector. You might go so far as to adapt or add to your existing business plans to show how they might line up with some of those priorities. This may then make it easier for local partners to “sell” the idea to other partners, suppliers, and customers, as well as get more cooperation from the government side.

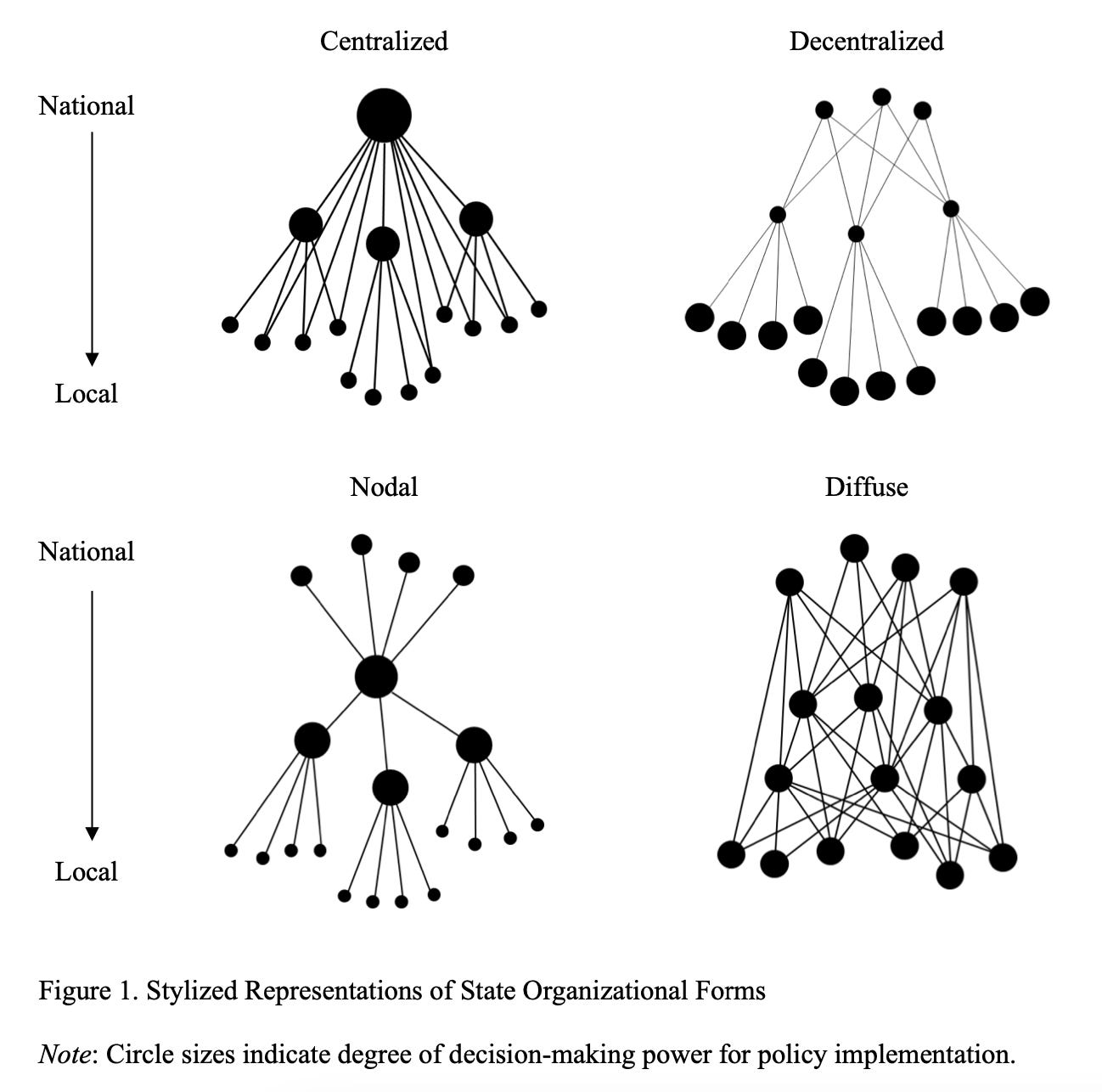

For doing business in India, state-level context matters a lot. I think there’s a lot more diversity among Indian states than there is among Chinese provinces, generally speaking. This not just language, which can differ very dramatically, but also culture more broadly. Heilongjiang and Guangdong feel more similar than Uttar Pradesh and Kerala. India’s northeast is quite distinctive, reminding me culturally of being in East Asia or Southeast Asia, not least because of their love for karaoke over there. And politically, much of the power resides at the state level in India. This is a long-standing feature of India’s federalized political system. So in terms of local partners, you might need to go “more local” in terms of working with different people who know different states well.

“My biggest piece of advice for anyone who wants to do business in China or India is to find local partners you feel comfortable with and who have a strong track record of working with international firms.”

Q: The next two questions come from the readers’ community. I often hear people say - India (shopping malls, consumer behavior, e-commerce ecosystem etc) is like China's 15 years ago ... I also use that, but it is quite flawed—where in their research do they really see similarities and what are the most obvious differences looking at China 15 or 20 years ago and India today?

One of the biggest differences that struck me the first time I went to India was the lack of skyscrapers. There are some in Mumbai and in Delhi you might find taller office buildings and condos in Gurgaon or Noida. But it’s not like my experience when I first went to Beijing where, on the taxi ride from the airport into the city, you pass by an endless parade of apartment building after apartment building. The skyline of even lower-tier Chinese cities is dominated by high-rises. So the type of urbanization that’s happening in India is just different than what happened in China 10 or 15 years before or what’s happening in China today.

But in terms of consumer behavior, there are many commonalities, including many that are not a “lag” between the two countries but happening in both simultaneously. Internet culture, smartphones, social media—especially among the youth—exploded in both countries. While the apps might be different—WeChat and Alipay in China, WhatsApp and YouTube in India—the intensity of the online world in these countries and their degrees of national distinctiveness sets them apart from other countries like the US or countries in Europe.

Shopping malls might have taken off a bit sooner in China, but they’re everywhere in India’s cities and very popular. Growing up in Los Angeles, I always found shopping malls kind of silly. But living in Delhi and Beijing, I found shopping malls to be an oasis of calm and air-conditioning whenever I needed to escape the bustle of the city.

So in general, I would say that there are some markets or sectors that are more reliant on having a larger, richer middle class—and this happened earlier in China. But there many other areas where trends showed up almost simultaneously in both countries. A trivial but fun example is the surge in coffee shops and microbreweries in cities from Beijing and Chengdu to Delhi and Bangalore. And then there are other areas where India and China have just taken different paths altogether, so it wouldn’t be useful to see one as simply some years behind the other.

Q: In theory, how [the infrastructure systems] are financed is interesting, though I think much more interesting is how the approvals work, and how effective/useful the infrastructure has been over time?

A lot of the infrastructure in both China and India is done by the government. Some people might not realize this, but the government also plays a large role in many sectors of the Indian economy, which is partly a legacy of an earlier Soviet-inspired system as I mentioned earlier. But there are some big differences. In China, a key source of financing is state banks, including the main national ones. They provide loans for state-owned enterprises as well as local governments to build railways, highways, ports, the power grid, and so on.

In India, the financing sources can vary. Sometimes they’re parliamentary budgets, which need to be negotiated and approved every year. Sometimes it’s the large private-sector business conglomerates like Reliance and Adani that might invest in ports or telecoms. India’s large construction firms, like Larsen & Toubro, are private whereas in China they’re SOEs, like China Railway Group Limited (CREC). Both countries face issues with financing volatility. In India, it might be shifts in Lok Sabha coalition politics. In China, it might be a sudden central government order to curtail infrastructure spending in certain provinces.

In terms of “good” infrastructure projects versus “bridges to nowhere,” one big thing I would point out is that both countries were infrastructure-poor, have large and dense populations, and have undergone rapid economic growth. This meant that there were many “easy wins” in terms of new infrastructure projects that would have a very high economic and social return on investment, like the Delhi Metro or the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed rail. I still remember near Delhi, I believe it was around Sultanpur just within the Haryana border, there was a long, narrow road that connected the main road to a whole community. It was too narrow for a car but packed full of autorickshaws and motorcycles, just barely squeezing past each other. Traveling on that road several times, each time I thought: “This would be the perfect place to build a wider road. There’s clearly so much traffic already, and even widening the road a bit and fixing some of the potholes would improve many people’s commutes every day.” India has been on an infrastructure boom lately, and I hope that this continues even across different administrations.

China today has probably gotten many of these “easy wins” in infrastructure already and has already passed the threshold of good into wasteful infrastructure in some areas, like some of the high-speed rail lines which are being driven by political motivations rather than meeting likely real demand. I would need to drill down on a case-by-case basis to really say. But even this is difficult to assess. For a rapidly growing economy like China’s with huge social trends like urbanization, what can look like a wasteful “bridge to nowhere” or “ghost city” one day might turn out to be a wise decision to build ahead of demand. The key is not to assess infrastructure or real estate construction merely on the basis of immediate uptake but on whether it will realistically line up with some future demand. 🔚

Hi Yangling, as an Indian I tend to agree with Kyle's understanding of India. I have also read a fair bit on China's history, economic transformation and have experienced that transformation ever since I moved to Shanghai last year. And as somebody who speaks Chinese, I feel I tend to understand the country and culture on a deeper level than would otherwise be possible.

On matters of infrastructure, I would emphasise, more than what Kyle did, on the substantial differences. I live in Shanghai, but I have also visited Beijing, Hangzhou and Chongqing. As an Indian, I do have to admit that the quality of infrastructure in those cities are far superior to that of any city in India. And the funny part is, I later learnt that Hangzhou and Chongqing are not even considered tier 1 cities in China. The infrastructure of Mumbai and Delhi, the two largest tier 1 cities of India, aren't close to what we find in China's tier 2 cities, let alone tier 1 cities.

In my view, this difference largely stems from two major differences - ease of land acquisition for large public infrastructure projects and governance & political structures. (I also think 户口 is another major point, but lets leave that for some other day).

Given that most of the land in India is privately owned it is very difficult to convince a whole neighbourhood to sell their land to the government so that it can build public infrastructure. Even if the government tries to more-than-fairly compensate those people, in many instances there has been opposition to such acquisition. Now you might wonder why would people not want more money for their land than its current valuation? It's kind of a no brainer. Right?

And this is where the second major difference - governance & political structures - becomes important. In India there are many political parties and civil society organisations and as Kyle emphasised regional politics is absolutely critical. Opposition parties, climate activists have a far greater role in India's policy-making. Sometimes, this is a good thing, but sometimes it makes the system incredibly inefficient, especially with regard to infrastructure building. I can find you umpteen number of examples where these stakeholders have mislead (or according to them rightly lead) the local landowners, a lot of whom are farmers, to oppose land acquisition despite a fair compensation. And if you can't acquire land quickly, you can't build infrastructure as fast as China did.

That's the gist of the problem, from my pov.

Finally, I personally also tell my Chinese friends here that India is about 25 years behind China with regards to infrastructure, in some places maybe many more years. I have also heard many mid-age Chinese people who have visited Delhi and Mumbai say that those cities today look like what they experienced Shanghai to be when they were 30 years old. I don't know if I am right, but I hope ultimately Indians will also experience this first class infrastructure like many Chinese do.